The Inca: How did they construct an empire without the wheel?

Inca Empire: Construction Without the Wheel?

Nestled within the imposing Andes Mountains, where peaks pierce the clouds, arose the Inca Empire, Tawantinsuyu—the Land of the Four Quarters. Originating modestly in the 13th century AD, it expanded to encompass over a hundred diverse societies, governing an estimated ten million people by the 15th century. Their dominion stretched from present-day Colombia to northern Argentina and Chile. They erected elaborate stone cities, extensive road networks, and sophisticated agricultural systems. The paradox lies in how this civilization achieved such monumental feats without the use of the wheel for transport or construction, and without possessing iron for tool and weapon manufacturing. How did they manage this vast empire, construct these magnificent structures, and provide for their people, utilizing only bronze, copper, stone, and the strength of a cohesive social organization? Could these very limitations have been the key to their power? This is the enigma we will attempt to unravel, revealing the ingenuity behind what initially appears to be a constraint.

The Great Inca Road: Qhapaq Ñan

How could this sprawling empire maintain cohesion? The answer lies in a unique engineering marvel: the Great Inca Road, or Qhapaq Ñan. More than just a road, it was an intricate network of interconnected pathways. Over 40,000 kilometers stretched across the rugged Andean terrain, from present-day Colombia in the north to Argentina in the south. Imagine roads paved with stone, ascending towering mountain peaks, traversing deep valleys, and cutting through arid deserts. The objective was not merely to connect cities, but to exert absolute control. The Qhapaq Ñan was a vital artery. It enabled armies to move swiftly and effectively to quell rebellions and expand influence. Envision the Chasqui messengers traversing these roads, relaying messages and royal decrees with remarkable speed, covering distances of up to 240 kilometers per day in a precise relay system. The roads were not solely for military and communication purposes; they facilitated trade and the exchange of resources between different regions of the empire. Agricultural crops, textiles, minerals, and other essential goods traversed these routes, fostering self-sufficiency and economic prosperity. Furthermore, the Qhapaq Ñan served as a conduit for disseminating Inca culture and their language, Quechua, contributing to the empire’s unification and cohesion. Contemporary studies, such as those conducted by the UNESCO team during the Qhapaq Ñan’s inscription as a World Heritage Site in 2014, highlight more than just an engineering accomplishment; it is an embodiment of Inca ingenuity in social organization and logistical management. Did this not enable them to overcome formidable environmental challenges and build a great empire without the need for iron?

Agricultural Terraces: Engineering a Verdant Landscape

Complementing the Qhapaq Ñan, the agricultural terraces stand as further compelling evidence of the Inca people’s genius. The rugged Andes Mountains presented a challenging agricultural environment, but the Inca, with remarkable ingenuity, transformed them into a verdant landscape through a complex and sophisticated agricultural system. Instead of succumbing to the challenge of directly cultivating steep slopes, they meticulously carved them into flat terraces, supported by robust stone walls that have endured through time. These ingenious terraces not only prevented the erosion of valuable soil but also created precise microclimates, allowing for the cultivation of a diverse range of crops in close proximity. The key innovation lay in their sophisticated irrigation system. Rainfall alone was insufficient to sustain these terraces, so the Inca constructed an intricate network of water channels, transporting water from glaciers and mountain springs to each terrace. These channels, carved with meticulous precision into solid rock, were designed to distribute water evenly, accounting for the specific water requirements of each crop and soil type. This was not merely brilliant engineering, but a profound understanding of soil science and climatology. The Inca experimented with different types of soil and natural fertilizers, including nutrient-rich guano and sardines, to optimize crop yields. They also understood the importance of crop rotation, changing the crops planted on each terrace periodically to maintain soil fertility and prevent pest infestations. Consider, for example, the Moray fields near Cusco, where the terraces form concentric rings descending to a depth of 150 meters, creating significant thermal variations of up to 15 degrees Celsius. These fields were not merely farms, but sophisticated agricultural laboratories, where they experimented with cultivating different types of plants in diverse climatic environments, seeking the optimal crops that could thrive in the Andes. These were truly advanced agricultural experiments, centuries ahead of their time.

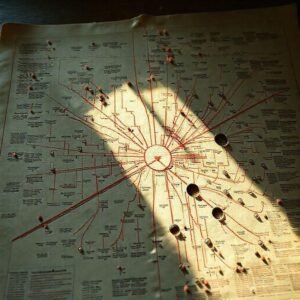

The Quipu System: Accounting Without Writing

While the Moray fields served as agricultural laboratories, the quipu system was the organizational framework that managed the flow of this abundance. Imagine a complex system of knotted cords, each knot representing a numerical value, and each color indicating a specific commodity or category. The quipu was not merely an accounting tool, but a comprehensive record of the empire, retaining details of taxes, population censuses, and even significant historical events. But was the quipu simply about numerical data? Contemporary scholars believe it was more complex than previously understood. In addition to numbers, the knots and arrangements may have conveyed non-numerical information, perhaps names, narratives, or even linguistic symbols. Imagine each strand of the quipu representing a village, and each knot representing its population, the amount of corn stored, and the number of warriors available for service. This information was vital for ensuring the efficient distribution of resources, organizing collective labor, and planning military campaigns. The quipucamayoc, or keeper of the quipu, was a pivotal figure. They underwent years of training to decipher these complex records and were responsible for maintaining the accuracy and updating the information. The quipucamayoc was an accountant, historian, and statistician all in one, their knowledge essential for the empire’s stability and prosperity. Unfortunately, the Spanish conquistadors destroyed many of these quipu, considering them pagan instruments. However, the remaining examples offer us a glimpse into the ingenuity of an astonishing accounting system, a system that allowed the Inca people to manage a vast empire without the need for writing. Does this not demonstrate that ingenuity knows no bounds?

The Mita System: Collective Labor and Social Cohesion

Having explored the intricacies of the roads and the quipu, we now turn to the core of Inca power: their cohesive social system. This system, which prioritized collective labor, underpinned the construction of their empire. It was not merely a matter of gathering manpower, but a sophisticated form of social engineering, based on the mita system, or mandatory labor. The mita was not slavery; it was an obligation for every adult male in the empire, serving the state for a specified number of days per year. But it was more than just a labor tax; it was a mechanism for distributing resources and tasks equitably among different regions. While some participated in building agricultural terraces, others engaged in mining, weaving textiles, or constructing temples. Consider, for example, the construction of Sacsayhuamán, the majestic fortress overlooking Cusco. It is estimated that its construction took decades and required the participation of tens of thousands of workers, who transported massive stones from quarries kilometers away, without the use of wheels. How was this possible? The mita system facilitated the organization of this immense undertaking, providing food and shelter for the workers, and coordinating their efforts under the supervision of skilled architects. But the mita was not just a tool for construction; it was also a mechanism for fostering unity and integration among different regions of the empire. When workers from different regions collaborated on a single project, they exchanged knowledge and experiences, and learned about each other’s cultures, fostering a sense of belonging to a unified entity. This sense of unity, coupled with the efficient mita system, is what allowed the Inca to achieve remarkable engineering and social achievements, without the need for iron or wheels. Was this social system not their greatest innovation?

Lessons from the Inca

The Inca’s lack of iron or wheels did not impede their ability to achieve remarkable architectural feats; rather, this very constraint may have motivated them to develop unique construction techniques that defied conventional understanding. Instead of relying on brute force, they employed precise engineering, meticulous planning, and collective collaboration to achieve seemingly impossible results. They polished the stones with extreme precision and placed them side-by-side without the use of mortar, forming robust walls that withstand seismic activity. They understood the properties of materials and used them strategically to achieve maximum stability and durability. The Inca legacy continues to inspire us today. They demonstrated that ingenuity does not depend on advanced technology, but on creativity, organization, and the ability to adapt to challenging circumstances. They built a great empire and left behind architectural, agricultural, and social treasures that testify to their extraordinary capacity to innovate and overcome obstacles. We have uncovered some of the secrets of the Inca and challenged the notion of their technological backwardness. But the question remains: what lessons can we learn from this civilization, in our contemporary world facing similar challenges? What parallels exist between the challenges faced by the Inca and the challenges we face today in terms of sustainability, social organization, and innovation? Share your thoughts in the comments, and do you believe we underestimate other civilizations because of their lack of modern technology?