The Library of Alexandria: A Single Blaze or a Slow Demise?

Library of Alexandria: Fire or Gradual Decline?

Introduction to the Legend of the Great Fire

Alexandria, a name synonymous with knowledge and wisdom throughout history, is most notably associated with its legendary library. However, the prevailing image is often not one of thriving scholarship, but rather a catastrophic conflagration consuming invaluable treasures. The notion of a devastating fire obliterating the library and its legacy has become deeply entrenched in the collective consciousness. While evocative, this image represents a significant oversimplification of historical events. The question of whether Alexandria truly suffered a single, all-consuming fire has fueled numerous conspiracy theories and ideological narratives, attributing blame to figures ranging from Julius Caesar in 48 BC to early Christians and even the Islamic conquest in the 7th century AD. However, the historical reality is more nuanced and less dramatic. This is not a tale of a singular, sudden catastrophe, but rather a narrative of gradual decline, characterized by political neglect, shifting intellectual priorities, and an irretrievable loss of knowledge that cannot be solely attributed to fire.

The Golden Age

The concept of the library originated with Ptolemy I Soter, one of Alexander the Great’s generals who inherited control of Egypt in 323 BC. It was conceived not merely as a repository of books, but as an ambitious political and cultural endeavor. The objective was to establish Alexandria as a preeminent global center of knowledge, rivaling Athens and other established intellectual hubs. The library’s foundation was established within the Temple of the Muses, dedicated to the goddesses of arts and sciences, which functioned as a comprehensive university, encompassing lecture halls, laboratories, and expansive gardens. The library reached its apex under Ptolemy II Philadelphus, who significantly expanded its holdings and dispatched expeditions throughout the known world to acquire valuable manuscripts. He is reputed to have acquired entire book collections at auction and even borrowed official manuscripts from other nations under the pretense of copying, often retaining the original and returning only the copy. Demetrius of Phalerum, the Athenian philosopher and politician who sought refuge in Alexandria, played a pivotal role in collecting and meticulously organizing the books and is credited with proposing the creation of the Great Library. The library’s collection extended beyond Greek literature, encompassing works from diverse cultures, meticulously translated into Greek, the lingua franca of the Hellenistic world. This included translations of the Hebrew Torah, known as the Septuagint, as well as works from Persia and India. The library served not only as a cultural monument but also as a vibrant center for scientific research, attracting brilliant mathematicians such as Euclid and Archimedes, and pioneering geographers such as Eratosthenes, who calculated the Earth’s circumference with remarkable accuracy. The library flourished due to the consistent flow of resources and the ambitious vision of the Ptolemaic rulers, who recognized knowledge as a form of power comparable to military strength. It served as a beacon of scientific inquiry, attracting leading minds from across the globe and contributing significantly to the advancement of human civilization. However, this golden age was not destined to endure.

The Beginning of the End

Following the death of Cleopatra VII in 30 BC and Egypt’s incorporation into the Roman Empire, the Library of Alexandria began to experience a period of gradual decline. This decline was not a sudden collapse, but rather a series of cumulative setbacks. The Roman rulers did not prioritize the library to the same extent as the Ptolemies. Once a symbol of Hellenistic power and culture, it became merely a component of a vast Roman province. Financial resources steadily diminished, and the library was relegated to a secondary position in the Roman Empire’s budget. Under Emperor Augustus, funding allocations began to decrease, impacting the library’s ability to acquire new manuscripts, compensate scholars, and maintain its facilities. Furthermore, Alexandria itself experienced political instability and frequent civil unrest. In 391 AD, Emperor Theodosius I issued a decree prohibiting pagan religions, leading to the destruction of the Temple of Serapis, which housed a branch library affiliated with the Great Library. While this event did not directly destroy the main library, it signaled a deterioration of the cultural and intellectual climate in the city. Conflicts between various Christian sects and frequent popular unrest destabilized the city and diverted resources that could have been used to preserve the library. Instead of supporting science and knowledge, the focus shifted to internal conflicts, leading to neglect and gradual deterioration. This gradual decline was not solely attributable to financial constraints, but also reflected a shift in intellectual priorities. Alexandria, once a leading center of science and philosophy, began to cede its position to other centers within the Roman Empire.

Conflicting Accounts

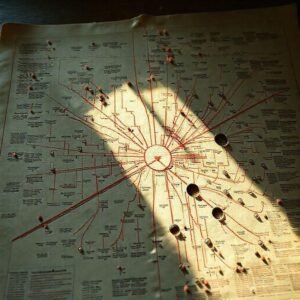

The mention of the fire of the Library of Alexandria immediately evokes an image of a catastrophic event resulting in total destruction. However, the historical record is far more complex. Multiple accounts of fires in Alexandria exist, but conclusive evidence directly linking any of them to the destruction of the Great Library is lacking. The most widely cited account dates back to 48 BC, during Julius Caesar’s siege of Alexandria. Some Roman historians report that Caesar set fire to enemy ships docked in the harbor, and the flames spread to nearby warehouses, potentially containing valuable manuscripts. However, these same historians do not explicitly state that the Great Library itself was consumed by the fire. The Roman historian Seneca the Younger, writing in the first century AD, mentioned the burning of 40,000 manuscripts, but did not specify their precise location. Whether these manuscripts were part of the Great Library or stored in other warehouses around the port remains an open question. Another account attributes a fire to 270 AD, during the reign of Emperor Aurelian, when he suppressed a major rebellion in Alexandria. However, details remain scarce, and the connection to the library remains uncertain. Some contemporary scholars suggest that the library had already begun a gradual decline long before this period, due to accumulated neglect and chronic underfunding under Roman rule. The claim that Christians destroyed the library in 391 AD, led by Patriarch Theophilus, as a retaliatory act against paganism, remains unsubstantiated and largely speculative. While Theophilus did order the destruction of the Temple of Serapis, evidence that this led to the complete destruction of the library is weak. These conflicting accounts cast doubt on the notion of a single, devastating fire and suggest that the fate of the library was more complex and multifaceted.

Lack of Resources and the Shift of Intellectual Centers

Fire alone was insufficient to extinguish the flame of Alexandria. By the fourth century AD, papyrus, the primary writing material, began to become increasingly scarce, hindering the library’s ability to thrive. Egypt’s monopoly on papyrus production, coupled with exorbitant taxes imposed by the Roman Empire, made it an expensive commodity, difficult for libraries and scientific centers outside Egypt to acquire in large quantities. This shortage significantly impacted the library’s ability to grow and expand compared to other libraries within the Roman Empire. Concurrently, new intellectual centers emerged in other cities, creating intense competition with Alexandria. Rome itself, and later Constantinople, became attractive destinations for scholars and philosophers, benefiting from imperial patronage and readily available resources. The Library of Constantinople, founded in the fourth century AD, amassed over 100,000 volumes and attracted numerous scholars who had previously favored Alexandria. Cities such as Athens and Antioch experienced a resurgence in their cultural prominence, capitalizing on Alexandria’s declining status. The pursuit of knowledge was no longer confined to a single city, but rather dispersed throughout the ancient world. This distribution of knowledge contributed to the marginalization of Alexandria’s role and diminished its importance as a singular center of learning.

The Remaining Legacy

The decline of the Library of Alexandria represents not merely the loss of a collection of rare manuscripts, but a poignant reminder of the fragility of knowledge in the face of neglect and political rivalry. While cities such as Constantinople, Athens, and Antioch were experiencing a cultural renaissance, Alexandria became a victim of intellectual stagnation and a decline in investment in knowledge. These events underscore the critical importance of sustained financial support and a stable political environment for the flourishing of any scientific center. The rise and fall of Alexandria offer valuable lessons regarding the crucial role of freedom of thought and expression. During the golden Ptolemaic era, the library prospered due to a climate of relative tolerance that allowed scholars and researchers from diverse cultures and backgrounds to freely exchange ideas. However, as successive empires exerted greater control, restrictions were gradually imposed on intellectual freedom, inevitably leading to a decline in innovation and creativity. Today, we must learn from the mistakes of the past. Preserving knowledge requires not only the collection of valuable books and manuscripts, but also, and more importantly, the cultivation of a genuine culture that values scientific inquiry and encourages critical thinking. We must always remember that knowledge is power, and its loss can have profound consequences for the future of humanity. The story of the Library of Alexandria serves as a cautionary tale, demonstrating that neglect and restrictions on freedoms can lead to the destruction of even the most impressive civilizational achievements.

Conclusion

The Library of Alexandria did not succumb to a single, devastating fire, but rather to a confluence of events and changes that precipitated its gradual decline. Instead of focusing solely on the narrative of a sudden fire, often attributed to Julius Caesar in 48 BC, we must adopt a broader perspective and consider the larger historical context. The erosion of financial support under the Roman emperors, the shift of the intellectual center of gravity to cities such as Rome and Antioch, and the severe shortage of Egyptian papyrus that intensified in later centuries all contributed to undermining the library’s position. Even the closure orders issued by Emperor Theodosius I for pagan temples in 391 AD, which