The Library of Alexandria Conspiracy: Were Significant Truths Suppressed?

Library of Alexandria: Lost Knowledge & Conspiracy?

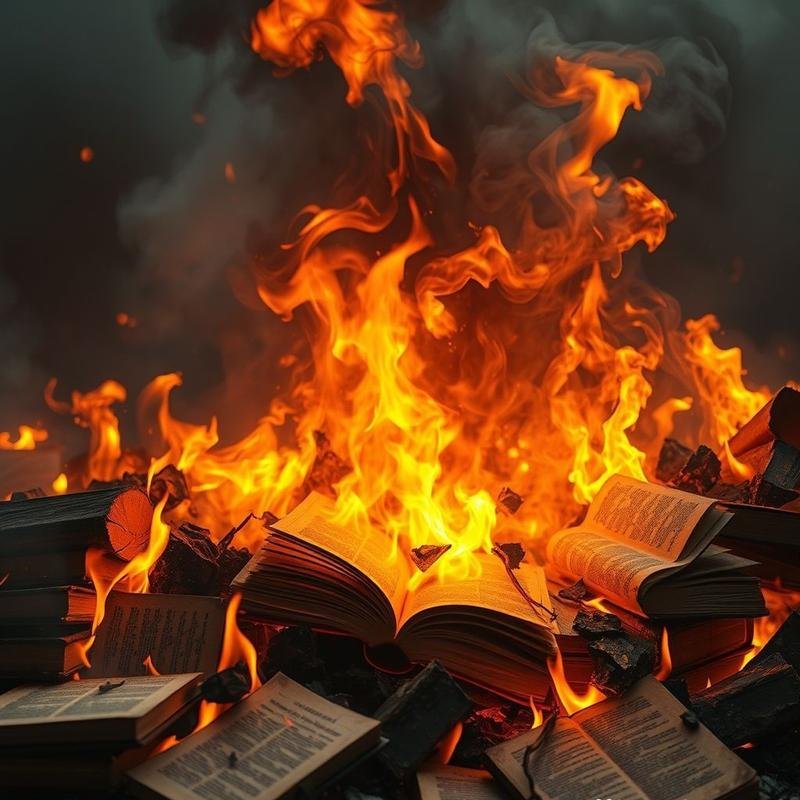

The Library of Alexandria is believed to have been destroyed by fire, but was this merely an accident? Or were dangerous secrets, capable of altering the course of history, permanently lost?

A Beacon of Knowledge

Alexandria, a majestic city, stood as a beacon of knowledge during an age of ignorance. It was here, at the confluence of Eastern and Western civilizations, that the unparalleled Library of Alexandria was established. More than just a repository of books, it was a vibrant center of intellectual activity, housing an estimated four hundred thousand to seven hundred thousand manuscripts, treasures of knowledge collected from across the known world.

The decree of Ptolemy III embodied a genuine passion for learning. Legend has it that every ship docking in Alexandria was required to surrender its books for copying, with the original placed in the library. Imagine: each manuscript, each papyrus, each record, representing a thought, a story, a scientific discovery, becoming part of this grand institution.

The Intellectual Giants Within

Within its walls, prominent scientists emerged, reshaping the course of history. Euclid made significant contributions to geometry, laying the foundations still taught today. Archimedes, a genius who defied the laws of physics, invented war machines that astounded the world. Eratosthenes dared to calculate the Earth’s circumference with remarkable accuracy, two millennia ago.

The Musaeum was not simply a library, but an integrated scientific complex, a temple dedicated to the Muses, complete with lush gardens, a zoo, and spacious lecture halls. It served as a center for research and discovery, where brilliant minds converged and exchanged innovative ideas in an environment that fostered creativity and innovation.

Theories of Destruction

But what became of this great institution? Fires, attacks, invasions… Multiple theories attempt to explain this tragic loss. The fire of Julius Caesar in 48 BC, the attacks by religious zealots in the late fourth century AD, the Islamic conquest in the seventh century AD – although directly linking the Islamic conquest to the library’s destruction remains a controversial interpretation. Each represents a possible scenario, and each raises further perplexing questions.

Seneca the Younger, the Roman philosopher, lamented the burning of forty thousand books in Alexandria during Caesar’s siege, noting that the books were stored in a warehouse, not necessarily within the main library, and describing the loss as a “monument of the genius of past generations.” Forty thousand books, representing the intellectual essence of entire generations, reduced to ashes.

Conspiracy or Accident?

But what if it was not merely a random accident? What if a deeper motive existed, a conspiracy brewing in secret? What if some of the ancient texts housed within the library contained dangerous, forbidden information, threatening the foundations of power and prevailing beliefs? Advanced scientific knowledge, alternative historical theories, prohibited religious texts… Did the library contain secrets that some sought to suppress? Was the fire of Alexandria simply a smokescreen to conceal a greater crime? This remains speculation.

The Vision and the Beginning

The Great Archive, a beacon illuminating the path to knowledge, emerged in the third century BC as a bold dream, perhaps inspired by Ptolemy I Soter, or encouraged by his son, Ptolemy II Philadelphus. It was not merely a collection of manuscripts, but an ambitious vision to gather all the world’s books under one roof. Imagine the scene: giant merchant ships docking in the port, carrying not only precious goods, but even more valuable treasures – treasures of knowledge, manuscripts carefully purchased or even forcibly added to the ever-growing collection.

Demetrius of Phaleron, a student of Aristotle, played a pivotal role in this remarkable beginning, providing valuable advice to Ptolemy I on the initial organization of the library. The library was not an isolated entity, but an integral part of a larger, more comprehensive complex, the Musaeum, a research institute dedicated to the Muses, goddesses of the arts and sciences. Here, brilliant minds flourished, and the boundaries of human understanding expanded to new horizons.

Zenith and Organization

The library reached its zenith with an estimated holding of between four hundred thousand and seven hundred thousand precious manuscripts. Imagine this vast repository of information, representing a rich intellectual heritage from various ancient civilizations. Zenodotus of Ephesus, the first librarian, laid the groundwork for organizing this immense collection. Callimachus, the poet and encyclopedic scholar, created a comprehensive catalog, a bold attempt to structure this vast ocean of knowledge.

Eratosthenes, the brilliant mathematician and geographer, left an indelible mark on the history of science. However, the library’s contributions extended beyond abstract theorizing. Scholars of the Musaeum made remarkable progress in diverse fields. Euclid’s enduring works in geometry, which laid the cornerstone of modern mathematics, were a direct result of this thriving scientific environment.

The Fading Brilliance

In the complex twists and turns of history, where the threads of power and knowledge intertwine in an eternal dance, Alexandria stands out as a glittering gem, its brilliance captivating. But this brilliance soon began to fade, like a shooting star disappearing from the sky, before the resounding rise of Rome. In 48 BC, Julius Caesar set fire to his fleet, and the flames spread uncontrollably towards the city. Whispers of concern circulated among the populace, discussing potential damage to the precious collection of knowledge. But the question echoed through the city’s streets: was the fire merely a random accident, or a smokescreen concealing deeper and more sinister intentions?

From Center of Knowledge to Roman Province

By the first century AD, Alexandria had become a vital artery feeding Rome, that insatiable empire. The wheat of Egypt, a lifeline for the Roman Empire, flowed abundantly through the ports of Alexandria. Economic and strategic dependence gradually eroded the city’s independence, transforming it from a center of knowledge and cultural radiance into a mere subject Roman province under Claudius – a province closely watched and subject to Rome’s strict dictates.

But Alexandria was not just a granary; it was a melting pot of diverse races and religions. Greeks, Egyptians, Jews… Escalating tensions, fueled by ethnic and religious differences, provided the spark to ignite destructive violence. A massive Jewish revolt erupted in 115 AD, devastating large parts of the city, inflicting deep wounds that exacerbated divisions and deepened hatred. Philo of Alexandria, the eminent Jewish philosopher, described the Great Library as a treasure of human knowledge, a timeless testament to its value, but also a painful reminder of the fragility to which these treasures could be exposed.

Whispers of Heresy

Within the corridors of the Library of Alexandria, knowledge was not merely a collection of static facts, but a time bomb ticking slowly, threatening to undermine the solid foundations upon which the Roman Empire was built. Here, in this majestic scientific institution, bold minds dared to question sacred assumptions and offer explanations of the world that contrasted sharply with established doctrines that were considered inviolable.

Aristotle, for example, did not simply describe the universe as it was presented to him, but delved into the question of its true center. Did the sun and all the planets truly revolve around the Earth, as sacred religious texts claimed? Or was there another system, more logical and consistent, that placed the sun at the center of the vast universe? These questions, despite their apparent simplicity, boldly challenged the absolute religious authority that was based on the idea of the Earth’s centrality and the perceived cosmic importance of humanity.

Eratosthenes, far from engaging in abstract philosophical reflections, immersed himself in precise measurements of the physical world. Using a simple stick, a shadow, and complex mathematical calculations, he arrived at an astonishingly accurate estimate of the Earth’s circumference, far closer to tangible reality than anyone else believed at the time. This remarkable scientific achievement, firmly grounded in careful observation and practical experimentation, significantly diminished the credibility of fanciful mythological accounts of the origin and shape of the world – accounts that were often used to justify absolute political and religious power.

Herophilus, the daring physician who dared to transgress the forbidden and dissect human corpses, went even further. He accurately discovered that nerves transmit sensations and that the brain, not the heart or any other organ as previously believed, is the true seat of intelligence and thought. This groundbreaking discovery, made in complete secrecy for fear of violent repercussions, directly challenged the established traditional view of the soul and its place in the body, thereby threatening the authority of the clergy who falsely claimed to possess knowledge of the secrets of life and death.

And in the field of history, Manetho, the learned Egyptian priest, presented an alternative and completely different account of the history of ancient Egypt, which differed fundamentally from the dominant Greek and Roman narratives. This authentic Egyptian account, which may have been hidden within the manuscripts of the ancient library, clearly indicated the existence of a completely different historical understanding, implicitly questioning the validity of the official accounts that were primarily intended to justify invasion and occupation.

These bold challenges were not limited to the fields of science and history. The library also contained the works of Pyrrho, the skeptical philosopher who publicly questioned the existence of the gods themselves. This radical skepticism, considered a major crime in ancient Rome, represented a direct threat to the official religion of the state, and therefore to its dominant political authority.

Under the strict Roman censorship laws, which imposed severe restrictions on freedom of expression, these bold ideas were like time bombs threatening to undermine the established order.

The Ominous Night

The ominous night, the night of the fire of Alexandria… In the year forty-eight BC, while the flames of war consumed the city, a tale emerged of a massive fire that engulfed the Great Library of Alexandria. Historians attribute this disaster to Julius Caesar’s campaign, claiming that his burning ships ignited the port, and the flames spread to the neighboring warehouses that housed treasures of knowledge. Seneca the Younger mentions the burning of forty thousand volumes, a staggering number that transcends mere material loss, representing an intellectual tragedy.

But was that just a random accident in the midst of

Video

Images