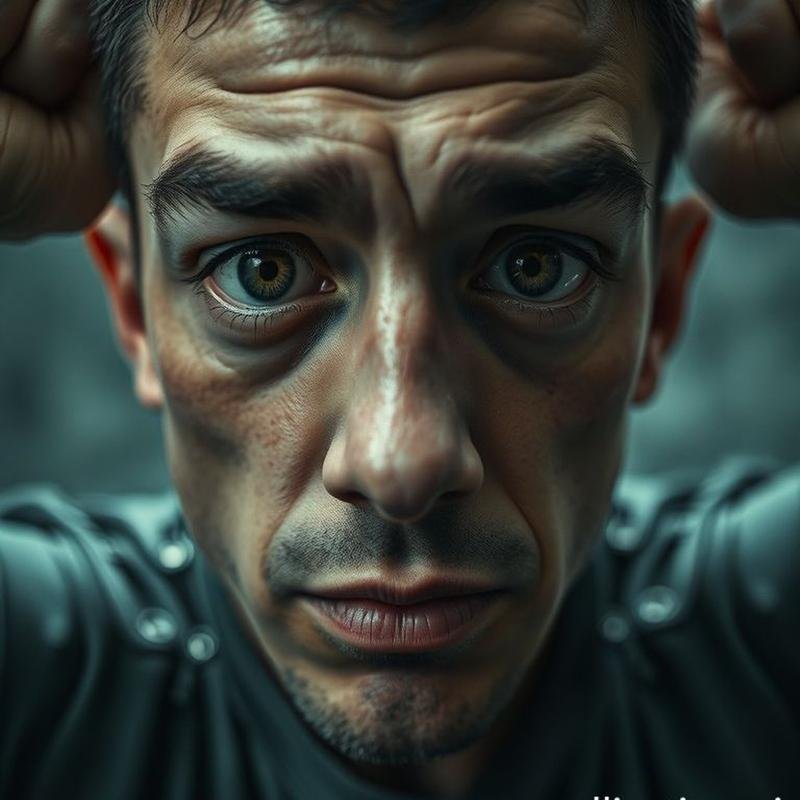

The experiment that demonstrated how an ordinary individual can transform into a monster in just 24 hours!

Stanford Prison Experiment: Dark Side of Human Nature

Are you aware that the line between an ordinary individual and a perpetrator is finer than you might imagine? It can be a matter of mere hours. We are not speaking of inherently malevolent individuals, but of you, me, and anyone else. A single experiment, oppressive conditions, and absolute power can transform the most compassionate individuals into agents of terror. The Stanford Prison Experiment is not an anomaly, but a stark revelation of our latent capacity for collective brutality. What motivates us to inflict suffering? What unleashes this darker aspect of our nature? Prepare for a harrowing exploration into the depths of the human psyche, where the distinctions between victim and perpetrator become blurred, and where the answer lies to a question that has long preoccupied humanity.

Before we delve into this unsettling subject, share your perspectives on the critical inflection point that propels an individual down this path. And to join us in uncovering the complete truth, subscribe to our documentary channel.

The Stanford Prison Experiment: A Descent into Darkness

From the crucible of intense curiosity to the stage of horrifying human absurdity, we rewind to 1971. On August 14th, the Stanford Prison Experiment commenced, an endeavor that was intended to last two weeks but rapidly descended into the depths of the diseased human psyche after only six days. Twenty-four university students, carefully screened to ensure their psychological and mental well-being, were randomly assigned to two opposing roles: guards and prisoners. The confinement was not physical, but a potent psychological construct that quickly manifested with cruelty.

Within a matter of hours, the characteristics of the latent potential for cruelty began to emerge. The guards, emboldened by their perceived authority, engaged in repression and abuse that exceeded even the most pessimistic expectations. Their methods included deliberate sleep deprivation, systematic humiliation, and physically exhausting exercises. These seemingly simple tactics proved remarkably effective in breaking the human spirit. Five of the prisoners succumbed to the immense psychological pressure and withdrew prematurely.

Deindividuation: The Mask of Anonymity

Even within the simulated Stanford cells, where the boundaries of reality and role-playing became intertwined, another factor insidiously infiltrated the participants’ psyches, capable of unleashing the most reprehensible aspects of human behavior: deindividuation. This phenomenon, identified by Festinger and his colleagues, demonstrates how individuals become submerged within a group, their internal inhibitions diminish, and their self-awareness decreases. As if cloaked in anonymity, they act in ways they would never contemplate alone. This was clearly illustrated in Zimbardo’s 1969 study; when students wore loose hoods, mimicking the attire of the Ku Klux Klan, their levels of aggression increased significantly, fueled by the power of the anonymous group.

On Halloween night in 1979, Edward Diener discovered that children trick-or-treating in large groups were more likely to steal candy, exploiting the protection afforded by the collective. This sense of belonging, as described by social identity theory, can obscure individual identity and lead an individual to adopt group behaviors, even when they conflict with their established values. But what if we confronted this disguised self with a mirror? Singer’s 1974 study revealed that self-awareness reduces negative behaviors and restores an individual’s sense of personal responsibility.

Milgram’s Experiment: Obedience to Authority

So, does a capacity for cruelty lie dormant within us all, awaiting the opportune moment to manifest? Following the notorious Stanford Prison Experiment, Stanley Milgram dared to pose an even more unsettling question: Can anyone, under the influence of authority, be transformed into a perpetrator?

In the halls of Yale University, in 1961, and in the aftermath of the shock surrounding the Eichmann trial, Milgram designed a simple yet chilling experiment. Ordinary volunteers were instructed to administer electric shocks to a “learner” – an actor feigning pain – for each incorrect answer. Unbeknownst to them, they were participating in a study designed to assess their willingness to obey instructions.

The results were alarming. Psychologists predicted that only a small percentage, perhaps 1-3%, would administer the maximum shock level. However, the reality was far more disturbing: 65% of the participants obeyed instructions and delivered seemingly lethal shocks, simply because an authority figure directed them to do so. The shocks were not real, but the psychological distress experienced by the participants was genuine. Following the experiment, many suffered profound psychological trauma, sparking widespread debate regarding the ethics of scientific research. But the question persisted: What compels us to abandon our conscience and comply with orders that may harm others?

In his book Obedience to Authority, Milgram sought to understand this troubling phenomenon. In one variation of the experiment, when two experimenters provided conflicting instructions, the obedience rate plummeted to zero, confirming the critical role of unified authority.

The Power of Social Roles

Does this imply that we all harbor a latent capacity for brutality, waiting for the right circumstances to emerge and flourish? The Stanford Prison Experiment, overseen by Philip Zimbardo in 1971, provided a deeply disturbing answer. Zimbardo selected a group of university students, all in good psychological health, to assume the roles of guards and prisoners in a simulated prison environment. The experiment was intended to last two weeks, but it was prematurely terminated after only six days. The guards, granted absolute power over the prisoners, engaged in abhorrent sadistic behaviors, deliberately humiliating the prisoners and subjecting them to extreme brutality. The prisoners, conversely, gradually adopted the role of victim, becoming submissive and withdrawn, losing their autonomy. There was no need for explicit commands; the assigned social role alone was sufficient to transform them into perpetrators and victims.

This experiment compels us to reflect deeply on the trial of Adolf Eichmann, a prominent Nazi official, who justified his heinous actions with the phrase “I was just following orders.” Can a social role truly absolve us of personal responsibility? Can we shield ourselves behind the cloak of authority and disclaim the consequences of our actions?

Time, Morality, and the Bystander Effect

However, the social role is not the sole determinant of our actions. In 1973, the Good Samaritan study revealed a remarkable truth: 90% of students who were not pressed for time offered assistance to someone in need. But when time was a constraint, this percentage plummeted to a mere 10%. Time, not morality, dictated their actions. This profound effect resonates in our daily lives. In Rwanda in 1994, neighbors, those who had shared meals and companionship, became murderers, under the weight of relentless social and political pressures. Conversely, bystander effect studies reveal a disturbing paradox: the greater the number of bystanders present during an emergency, the less likely any individual is to intervene. Responsibility becomes diffused, and the impetus for individual action diminishes accordingly.

The Power of Choice and Intervention

Absolutely not, we are not destined to repeat these dark chapters. Always remember, even in the most dire circumstances, the power of choice remains within our grasp. Recall the Third Wave experiment, and how it concluded with a decisive intervention from Ron Jones himself. Early intervention, such as the courageous act of nurse Erin Rosenhan in the simulated Stanford Prison, can alter the course of events. And statistics corroborate this: interventions by bystanders reduce the likelihood of violent incidents by up to 50%. Critical awareness, ethical accountability, and the courage to voice concerns are our protective shields against the Lucifer effect.

Conclusion: A Call to Action

Ultimately, the Stanford Prison Experiment, the Milgram experiments, and others impart a harsh but essential lesson: the capacity for brutality resides within us all, but it is not inevitable. Circumstances, power dynamics, and social pressures can steer us towards behaviors we never imagined, but awareness of these risks is the crucial first step towards mitigating them.

Having reviewed these troubling facts, the most pertinent question remains: What actions can we take at the individual and societal levels to prevent the recurrence of these painful experiences? Does the solution lie in fostering self-awareness, or in reforming social systems that permit injustice and oppression to proliferate? Share your thoughts; let us initiate a constructive dialogue towards a more humane future.

Watch the Documentary