The Aral Sea: A 20th-Century Catastrophe 📜🤯 | How the Fourth Largest Lake Became a Desert

Aral Sea Disaster: Death of a Lake

Did you know that a ship graveyard exists hundreds of kilometers from the nearest shoreline? In this episode, we investigate a devastating environmental catastrophe that transformed what was once the world’s fourth-largest sea into a barren desert, revealing how short-sighted economic policies extinguished the aspirations of entire generations, leaving fishing vessels to rust as silent monuments to the past. We will explore the story of the Aral Sea, not merely as an environmental tragedy, but as a stark warning to those who believe that nature can be exploited without limit.

Before we begin this exploration, please share your perspectives on the underlying causes of this disaster in the comments section. To gain a comprehensive understanding, subscribe to the channel and join us as we unravel the complete narrative.

The Aral Sea: A Dying Echo

The Aral Sea… a name that once resonated throughout Central Asia, synonymous with life and abundance. Today, it is a mere echo of its former self. In the 1960s, it was the fourth-largest lake globally, its vast expanse nearly the size of Ireland – 68,000 square kilometers of azure waters shimmering under the sun. Envision this immense body of water, an aquatic paradise supporting thousands of fishermen, harboring unique biodiversity, and serving as a vibrant economic center. A dynamic ecosystem, teeming with life.

However, this breathtaking vista was ultimately overcome by human greed and short-sightedness. As massive agricultural projects consumed the waters of the Amu Darya and Syr Darya rivers, the lifelines that sustained the sea, a gradual decline began to engulf its waters. Twenty centimeters… then fifty… then ninety centimeters per year! The water level plummeted, year after year, accelerating towards an inevitable disaster. Can you comprehend this precipitous descent?

By 2007, only 10% of this once-vast aquatic ecosystem remained, fragmented into four separate lakes, bearing witness to a fully realized environmental crime. Salinity levels surged from 10 grams per liter to over 100 grams, decimating aquatic life and transforming the sea into a saline wasteland. Muynak, formerly a thriving coastal city, is now a desolate desert, its rusting ships stranded dozens of kilometers from the nearest shore.

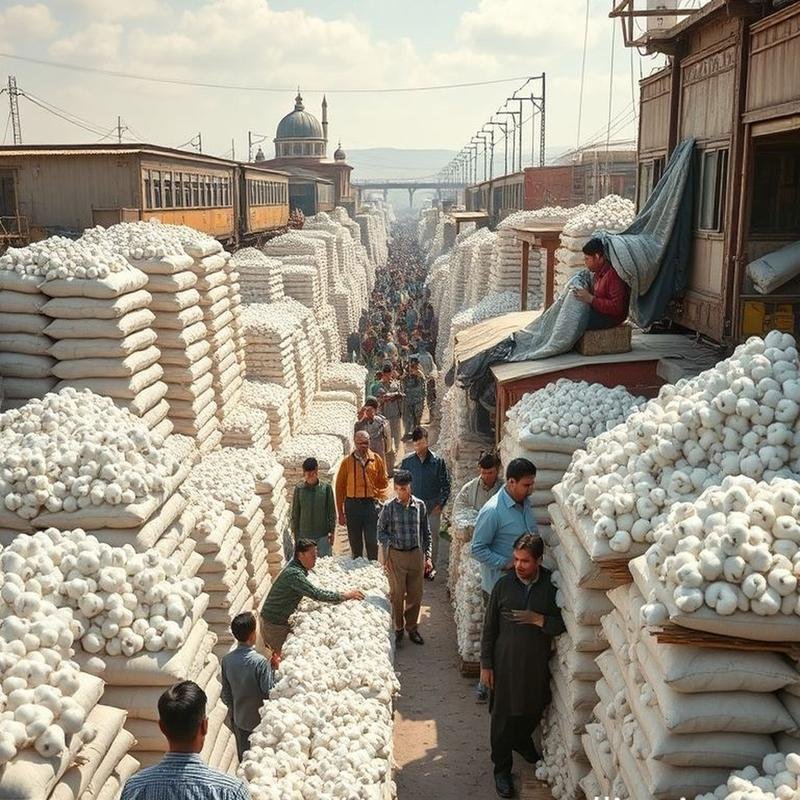

These rusting ships are not merely abandoned vessels; they stand as monuments to a tragic chapter in the history of the Aral Sea. A chapter authored by human actions, driven by the pursuit of “white gold,” the infamous cotton.

The Allure of “White Gold”: Cotton’s Deadly Thirst

In the 1920s, the Soviet Union initiated an ambitious, even reckless, project to transform Central Asia into a vast cotton plantation. “White gold,” as they boldly called it, was intended to bring prosperity and power. By the 1980s, Uzbekistan alone was responsible for producing two-thirds of the Soviet Union’s cotton, establishing itself as a major player in the global cotton market.

However, this artificial prosperity came at a significant cost, a cost borne by nature and future generations. Cotton is a water-intensive crop, demanding vast quantities of water. To satisfy this insatiable demand, the Amu Darya and Syr Darya rivers, the Aral Sea’s primary sources, were diverted from their natural courses. Initially, the amounts withdrawn were relatively modest, ranging from 20 to 50 cubic kilometers per year. However, with each successive cotton season, the demand intensified, reaching 60 cubic kilometers by the 1980s.

The problem was not solely the volume of water extracted, but also the inefficient methods employed. Dilapidated irrigation canals resulted in the loss of between 30% and 70% of the precious water through leakage and evaporation. Consider this egregious waste! Consider this deliberate negligence!

The Soviet government even contemplated absurd, even criminal, solutions, such as diverting a portion of the Siberian Ob River to Central Asia, but even this irrational plan was abandoned due to environmental and economic considerations. By 2000, the end was imminent.

The Point of No Return: The Karakum Canal

But before we delve into that tragic outcome, let’s revisit the critical point of no return. In the 1960s, a clear warning emerged, signaling the beginning of an engineering disaster that would fundamentally alter the region. The project to divert the waters of the Amu Darya and Syr Darya, the lifelines of the Aral Sea, was launched with full force. The objective? To transform the vast, arid desert into a verdant agricultural paradise, to cultivate cotton, the “white gold” that represented the Soviet Union’s illusory dream of prosperity.

In 1954, construction began on the Karakum Canal, a massive concrete structure extending over 1,300 kilometers across the deserts of Turkmenistan. This ambitious project, hailed as one of the largest irrigation projects in the world, began to extract vast quantities of water from the Amu Darya. It was intended to irrigate millions of hectares of new cotton fields, but the price was steep: an impending environmental catastrophe.

By the 1980s, the harsh reality became undeniably clear. Between 20 and 50 cubic kilometers of water were being withdrawn annually from the two rivers, leading to a catastrophic and alarming decrease in water flow to the Aral Sea. This was not merely a decline in water levels; it was the harbinger of a silent epidemic spreading across the region.

A Toxic Legacy: The Human Cost

Dust storms, carrying toxic salts and pesticides from the vast cotton fields, became a pervasive element of the air that people breathed. Respiratory illnesses increased dramatically, transforming lives into a constant struggle with shortness of breath and chronic coughing.

Toxic chemicals, the polluted legacy of the past that settled on the dry seabed, chemicals that had been used indiscriminately to combat agricultural pests, now permeated the dust and water, exacerbating the pervasive environmental pollution. Cancer rates, particularly liver cancer, rose alarmingly in communities near the shrinking sea, foreshadowing a bleak future.

Children, the most vulnerable, were the hardest hit. Studies revealed a shocking increase in birth defects among newborns in affected areas, widely attributed to water and food contamination. In the 1990s, infant mortality rates in the Karakalpakstan region surrounding the Aral Sea were among the highest in the former Soviet Union, exceeding 100 deaths per 1,000 live births, a devastating statistic. The lack of clean water further compounded the situation, leading to outbreaks of infectious diseases such as typhoid and hepatitis, further increasing the suffering of already vulnerable local communities. From the city of Muynak, once a vibrant port, we now see a desolate scene. Here, where ships once swayed gracefully on the shimmering water, their rusting hulks now lie stranded in the heart of the vast desert, silent witnesses to the collapse of an entire industry.

In 1960, the Aral Sea teemed with life, producing nearly 40,000 tons of fish annually, providing livelihoods for more than 60,000 people. Those prosperous days are gone forever.

By the 1980s, the fish had completely disappeared, forcing the canning factories in Muynak and Aralsk to close their doors permanently. Unemployment soared, and communities began to disintegrate. It wasn’t just the loss of jobs; it was the collapse of an entire way of life, a heritage lost to the wind. Salty dust storms, laden with deadly toxins from the dry seabed, swept across fertile agricultural lands, adding to the harsh reality. Economic losses are estimated at billions of dollars, leaving deep scars on the economies of Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan. Cities like Aralsk experienced a painful mass exodus, as residents abandoned their homes in a desperate search for employment elsewhere, leaving behind abandoned communities and decaying infrastructure.

Glimmers of Hope and Harsh Realities

As the Aral Sea faces its inevitable fate, efforts at human intervention have continued, offering a glimmer of hope. In 2005, the North Aral Sea project was implemented, revitalizing the northern part; the waters rose, and fish returned. The Kokaral Dam, standing as a formidable barrier, separated the recovering north from the deteriorating south, preserving what remained.

However, the question remains: are these efforts sufficient? The planting of saxaul, a hardy desert plant capable of withstanding harsh conditions, was a desperate attempt to combat desertification, but water scarcity hindered the achievement of the desired results. UNDP projects, despite their noble intentions, have had only a limited impact on communities ravaged by drought and desertification.

In the 1980s, a radical idea emerged: diverting Siberian rivers. An ambitious, costly, and controversial project, it was abandoned before it could be implemented, remaining a distant dream. And in 2011, a World Bank report confirmed what was already known: that fully restoring the Aral Sea was impossible. Therefore, efforts should focus on mitigating the catastrophic effects, rather than attempting to restore a lost dream. However, even with these limited efforts, the threat of pollution remains a constant concern.

A Warning for the Future

The dry seabed poses a significant environmental risk. But the tragedy of the Aral Sea is not an isolated incident; it serves as a stark warning that resonates in other parts of the world, foreshadowing a grim future that awaits us.

Consider Lake Chad, which has shrunk by an astounding 90% since the 1960s, a victim of excessive water consumption and accelerating climate change. Or the Dead Sea, whose level is declining at an alarming rate, a full meter each year, due to the diversion of the Jordan River, an environmental crime that raises serious concerns. And in the heart of Asia, the Mekong River basin faces increasing pressures that threaten the food security of millions of people, potentially leading to mass displacement and regional conflicts.

Beyond these disaster-stricken regions, even affluent California has experienced severe droughts, forcing it to implement stringent water conservation measures.