Evolutionary Psychology: Exploring the Roots of Superstitious Beliefs

Superstition & Evolution: Why We Believe

Why does the sudden appearance of a black cat trigger a racing heart, even within the confines of a modern SUV? Could our most seemingly irrational thoughts be vestiges of ancestral survival strategies? This episode explores the field of evolutionary psychology to understand how superstitions and peculiar beliefs may have once been critical for survival, examining whether they continue to serve a protective function or now impede progress.

Before we delve into the evidence, we invite you to share your initial perspectives in the comments section. To join us on this exploration of truth, please subscribe to the channel and support our ongoing investigation.

The Evolutionary Psychology Perspective

Having considered the enduring influence of the past on the present, let us now turn to the core of our discussion: evolutionary psychology. This discipline represents not merely the study of behavior, but a rigorous attempt to decipher the human brain itself. Envision the brain as a tool meticulously shaped by millennia of challenges, each convolution and structure precisely adapted to address the survival and reproductive imperatives faced by our forebears.

Evolutionary psychology is predicated on a fundamental principle: that our minds, like our bodies, have evolved through the process of natural selection. The contributions of evolutionary biologist Ernst Mayr were pivotal in the development of this concept. This implies that traits, both physical and behavioral, that enhanced the survival and reproductive success of our ancestors have been transmitted to subsequent generations. A prime example is the inherent aversion to bitter tastes, a psychological adaptation that protected our ancestors from consuming poisonous plants and has become ingrained in our genetic makeup.

Superstition as an Evolutionary Remnant

But how does this relate to superstitions? This is where the connection becomes particularly compelling. Natural selection not only refines physical responses but also molds cognitive processes. The fear of darkness, for instance, may be an evolutionary adaptation designed to safeguard our ancestors from nocturnal predators. Could superstitious beliefs, which appear illogical in the modern context, simply be remnants of these ancient adaptations, echoes of our ancestors’ strategies for survival in perilous and uncertain environments? This is the central question we aim to address.

Cognitive Biases: Whispers from the Past

Imagine our ancestors, not passively observing illuminated screens, but confronting volatile environments where instantaneous decisions determined their fate. In such circumstances, cognitive biases emerged as whispers from the past, a profound evolutionary legacy. Consider confirmation bias, the inherent inclination to favor information that reinforces pre-existing beliefs. The seminal 1979 study by Lord, Ross, and Lepper illuminated this pervasive human tendency. Picture yourself in the heart of a forest, convinced of the toxicity of a particular plant species. Would you risk testing this belief? Unlikely. This bias, despite its apparent simplicity, may have saved countless lives.

Then there is the availability heuristic, whereby events that are readily recalled are perceived as more probable than they actually are. The groundbreaking 1973 research by Tversky and Kahneman demonstrated how individuals overestimate the risk of airplane crashes, influenced by vivid and easily accessible memories. In ancient times, recalling a past natural disaster could facilitate optimal preparation for a similar event, thereby increasing the likelihood of survival.

Furthermore, we must acknowledge the Dunning-Kruger effect, the paradoxical phenomenon in which individuals with limited competence overestimate their abilities. In the unforgiving realm of survival, overconfidence may lead to perilous situations, but it could also provide a critical advantage. Even the illusory correlations identified by Chapman in the 1960s, where individuals perceive patterns and relationships that do not exist, may offer a hidden benefit. Imagine briefly glimpsing a predator lurking in the shadows. Even if it is merely an illusion, assuming its presence may be sufficient to save your life.

Error Management Theory and the Smoke Detector Principle

This encapsulates the essence of error management theory: our minds are predisposed to favor errors that minimize risk, even if these errors appear illogical on the surface. Consider a dating scenario. A study by Haselton and Buss revealed a notable discrepancy: men tend to overestimate a woman’s sexual interest, while women often underestimate a man’s level of commitment. Why this asymmetry? Because the consequences of error differ significantly. For a man, misinterpreting signals may result in a missed opportunity for mating. For a woman, it may lead to forming a bond with an unreliable partner.

The smoke detector principle further illustrates this concept. It is preferable to trigger a false alarm (fear of a non-existent threat) than to overlook a genuine fire, particularly when the cost of a false alarm is minimal.

Superstitions as Echoes of Ancient Strategies

This brings us to superstitions: avoiding walking under ladders, clinging to lucky numbers. These behaviors may seem absurd in the light of reason, but they may represent echoes of ancient survival strategies. The cost of adhering to these superstitions is typically low, while the perceived potential risks – bad luck, misfortune – can be significant. A study by Ono demonstrated that superstitious behaviors can develop even under entirely random conditions, where individuals mistakenly associate certain actions with positive outcomes. Is avoiding foods that have previously caused illness not another example? Even if the food was not the actual cause, this heightened caution could prevent a potential disaster.

Pareidolia: Finding Patterns in Randomness

Is this not precisely what defines our humanity? This extraordinary capacity to connect disparate elements, to discern patterns where others perceive only randomness? This very drive propels us forward, inspiring us to explore the uncharted territories of knowledge and experience. Yet, this remarkable trait, this fervent pursuit of meaning, also possesses a darker aspect.

Consider faces appearing in the formations of clouds or imprinted on a piece of toast. This is pareidolia, a deeply ingrained psychological phenomenon that compels our minds to perceive meaningful patterns within random stimuli. A 2009 study highlighted a compelling correlation, revealing that individuals experiencing anxiety are demonstrably more susceptible to this intriguing effect. Is it merely a flaw in the intricate machinery of the brain? Or could it be an ancient survival mechanism, resonating from the depths of our evolutionary past?

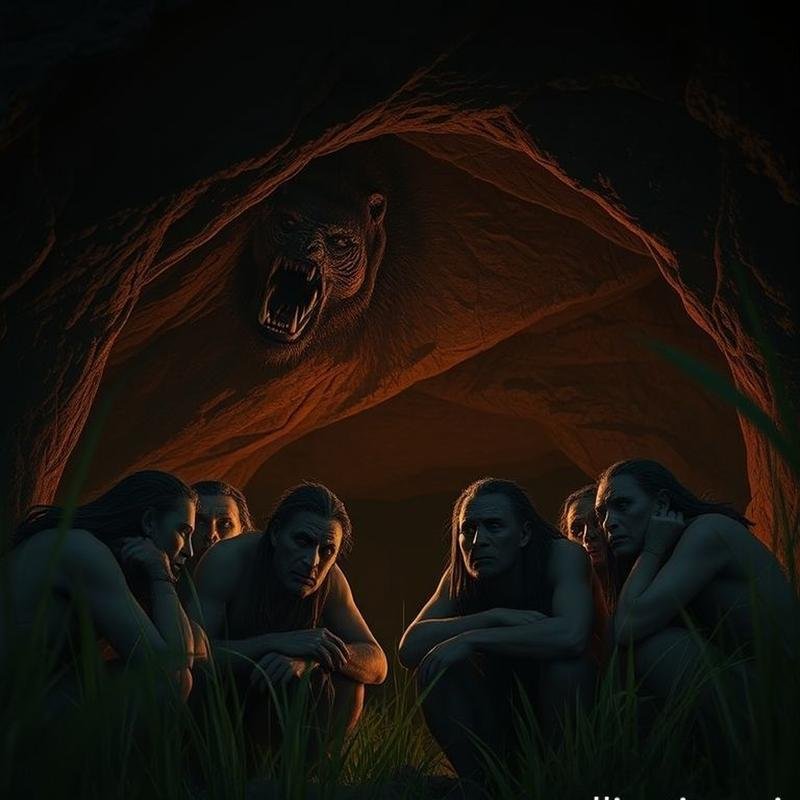

Evolutionary psychologists tend to favor the latter hypothesis. In the primordial eras of our species, the rapid detection of a potential threat, even if ultimately illusory, offered a distinct advantage over the catastrophic consequences of overlooking a genuine danger. Imagine our ancestors traversing the vast savanna, their senses attuned to the slightest rustle in the tall grass. Was it merely the whisper of the wind? Or the stealthy approach of a concealed predator? It was invariably wiser to investigate, even at the risk of triggering a false alarm.

Infants begin to recognize faces remarkably early in their development, a clear indication that this innate ability is woven into the fabric of the human brain. But what happens when this faculty exceeds its intended boundaries? What happens when we begin to discern patterns where none exist, or fabricate causal relationships where there is only coincidence? Here, in this fertile ground of cognitive misinterpretation, the seeds of superstitions and elaborate conspiracy theories begin to germinate and take root.

Superstitions as Social Glue and Coping Mechanisms

However, there may be another dimension to this narrative, a more optimistic perspective. Could these irrational beliefs, even superstitious ones, serve as a unifying force, unexpectedly binding us together?

The power of shared beliefs resides not necessarily in their veracity, but in their profound capacity to foster social cohesion. Imagine a primitive society whose survival depends on hunting. Before each perilous hunting expedition, they engage in elaborate rituals, donning ornate masks and chanting hymns that may appear bizarre and unfamiliar to us. But anthropologist Bronisław Malinowski astutely observed that these rituals were not merely an expression of fear, but a powerful means of fostering trust and vital cooperation among the hunters.

A groundbreaking study published in Science in 2008 emphatically corroborated this, demonstrating that individuals who participate in collective rituals, even if seemingly illogical, exhibit significantly greater cooperation in subsequent tasks. Psychologist Deniz Kandiyoti suggested in a 2009 study that religious and superstitious beliefs may have evolved, in part, as a means of distinguishing “us” from “them,” thereby strengthening intra-group cooperation. Societies with strong shared beliefs, even if unconventional, tend to be more resilient in overcoming crises and inevitable internal conflicts. This is what sociologist Émile Durkheim described as collective effervescence, where individuals experience a profound sense of unity with the group through shared religious rituals. Research has even indicated that groups that demand greater sacrifices from their members tend to be more cohesive and enduring in the long term. As Jonathan Haidt argues in his book The Righteous Mind, shared moral and religious beliefs function as a potent social adhesive.

But what if these superstitions are more than mere echoes of the past? What if they represent deeply ingrained coping mechanisms? Imagine yourself as an athlete preparing for a playoff game, or as a student on the cusp of a crucial exam. Can you simply disregard your lucky shirt or abandon your customary pre-competition rituals?

Intriguingly, research suggests that these superstitious actions may confer tangible benefits. In a 2010 study, individuals who engaged in superstitious behaviors before confronting a challenge performed better, suggesting that superstitions enhance self-confidence. Similarly, another study revealed that students who carried a lucky charm during a math test achieved higher scores. It may seem illogical, but these rituals provide us with an illusion of control in the face of the unknown.

Perhaps this explains why superstitions become more prevalent during periods of economic or social upheaval. Amidst uncertainty and heightened anxiety, we find solace in these behaviors to soothe ourselves and restore our sense of security. As terror management theory posits, superstitions help to alleviate existential anxiety by providing us with a sense of control over events beyond our influence. Can we not then assert that superstitions are akin to a placebo for the mind, offering the psychological comfort we desperately require in a world fraught with turmoil?

Conclusion

So, has the influence of superstition waned in the age of science? Has the power of these ancient beliefs to captivate us diminished? Disconcerting studies indicate that more than half of adults in the United States still subscribe to at least one superstition or believe in a phenomenon that defies the laws of nature. In 2020, a poll revealed that 26% of Americans