Did the Arab conquest eradicate hieroglyphic writing? 📜 The truth may surprise you.

Hieroglyphics’ Decline: Beyond the Arab Conquest

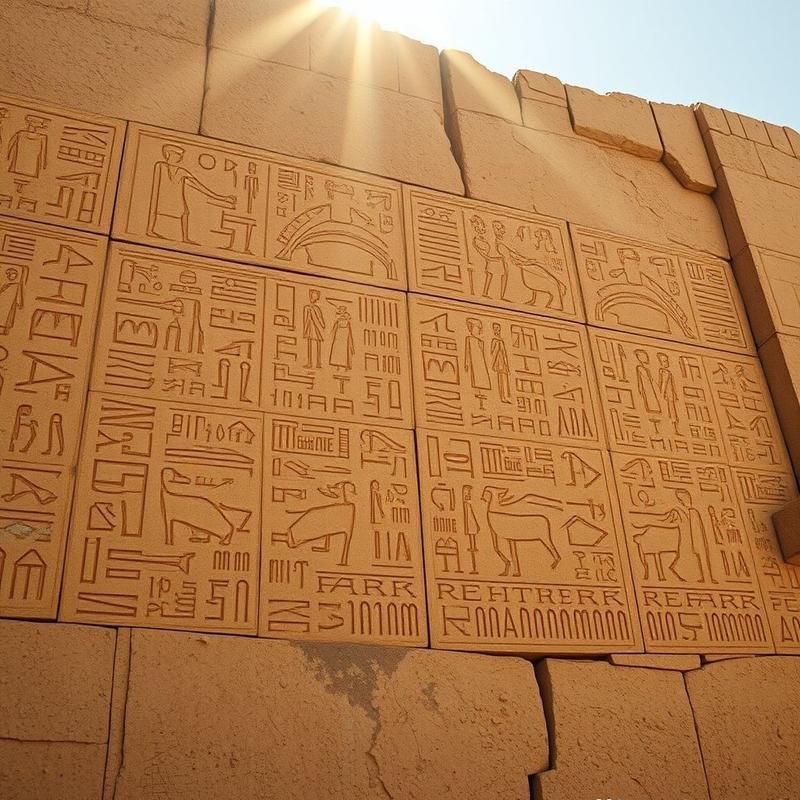

Was hieroglyphic writing not in a state of diminished use for centuries prior to the Arab arrival in Egypt? This seemingly paradoxical question highlights a frequently overlooked truth. The widely held belief that the Arab conquest marked the end of the pharaohs’ language is an oversimplification of a more nuanced historical narrative. What factors truly contributed to the decline of this sacred script? Was it solely military force, or were there other influences that permeated Egyptian society, gradually eroding a legacy that had endured for millennia? Embark on a journey into the complexities of history, where the threads of a subtle shift will be revealed. The key drivers of this shift are not solely external conquerors, but rather profound social and cultural transformations, and the rise of new alphabets that competed with hieroglyphics for linguistic dominance.

Before we proceed to present the compelling evidence, we invite you to share your perspectives in the comments section. And to ensure you don’t miss further insightful discoveries, please subscribe to the channel.

The Diminishing Use of Hieroglyphics

Hieroglyphics, that majestic script used to record the glories of the pharaohs on temple walls, were already in a state of decline when the initial signs of the Arab conquest appeared. Their use was gradually diminishing, giving way to other alphabets, such as Coptic and Greek. In the fourth century AD, Christianity gained prominence in Egypt, and the Coptic language, the final evolution of the pharaohs’ language but written in Greek script, rose to prominence. Coptic became not only a spoken language, but also the language of liturgy, the church, and daily life for Egyptians. This represents a profound societal transformation.

By the fifth century, the use of hieroglyphics had dwindled, confined to a small number of priests in remote temples. The last widely documented hieroglyphic inscription, dated August 24, 394 AD, was found in the Temple of Isis on the island of Philae. This inscription by the pagan king Esmet-Akhom stands as a silent testament to the end of a glorious era. It is important to remember that archaeological discoveries continue to be made.

Demotic script, the simplified form used for everyday and legal transactions, was also in decline. It, too, was fading as society changed. While some knowledge of hieroglyphics persisted within Coptic monasteries, it was regarded as part of the pagan past, a distant memory rather than a living language. It is worth considering whether these monks fully appreciated the value of what they preserved.

The closure of the Temple of Isis in Philae, by order of the Byzantine Emperor Justinian I in the sixth century AD, significantly contributed to the decline of hieroglyphics. This closure reduced opportunities for the use of hieroglyphic writing. When the Arab conquerors arrived in 641, they encountered not a single dominant language, but a mixture of languages and dialects, and a society with potentially diverse perspectives on the new language and culture.

Linguistic Transformations Before the Arab Conquest

The Arab conquest was merely the final chapter in a long series of significant linguistic transformations. Prior to the arrival of the conquerors, Egypt was already undergoing a complex process of linguistic replacement, reflecting cultural and religious shifts. How did the Coptic and Greek languages contribute to the decline of hieroglyphics, the language that had dominated Egypt for thousands of years?

In the first century AD, Coptic emerged as a spoken language, the final stage of ancient Egyptian, and contained the seeds of a radical transformation. Instead of relying on the complex hieroglyphic writing system, Coptic adopted the Greek alphabet, with the addition of seven letters derived from Demotic to represent authentic Egyptian sounds. This simplification, while seemingly technical, had a profound impact on the language’s future.

By the third century AD, Coptic had become a widely used literary language, competing with hieroglyphics, which had begun to lose its prominence. Consider the volume of influential Christian religious, legal, and personal texts that began to be produced in this new language. Hieroglyphics, closely associated with the temples of the pharaohs and their ancient rituals, gradually receded before the rising tide of Coptic.

We must also acknowledge the crucial role of Greek, the language that shaped Egypt during that era. Since the Ptolemaic period (305-30 BC), Greek had become the language of administration and education, the language of power and influence. Imagine the educated Egyptian elite, both men and women, speaking and writing Greek fluently, using it in complex trade and daily life. The Fayyum Papyri, and particularly the valuable Oxyrhynchus Papyri, reveal a world of personal letters, commercial contracts, and government records written in Greek.

The Arab Era and the Rise of Arabic

With the turbulent changes that swept through Egypt in 641 AD, when Alexandria fell to the army of Amr ibn al-Aas, a new era began: the Arab era. But did this conquest signal the end of hieroglyphics? The reality is more complex. By the eighth century AD, Arabic had become established as the language of official administration, displacing Greek and Coptic from official documents. However, this transformation was not immediate, but rather the culmination of a long-term process.

The Pact of Umar, a document that continues to generate controversy and whose attribution to Caliph Umar ibn al-Khattab is questioned by many historians, reflects an attempt to regulate the relationship between Muslims and the People of the Book. Interpretations of this document vary; some view it as aiming to protect the Copts, while others see it as imposing restrictions on them. Despite the ongoing debate, life continued along new and evolving paths. The Egyptianization movement, which predated the Arab conquest, continued to revive authentic Egyptian identity, clearly manifested in Coptic architectural arts that preserved timeless Pharaonic elements. Some Copts even retained their ancient Egyptian names, in a silent act of defiance against time.

The decline of Coptic as a spoken language by the seventeenth century resulted from complex social and economic factors, and it cannot be asserted that there was no form of pressure or discrimination. Classical Arabic profoundly influenced the spoken language, giving rise to Middle Arabic, the distinctive Egyptian dialect that still retains Coptic words today. It is believed that some words, such as “tata” (step) and “awa” (moment), may be of Coptic origin, but this requires further in-depth linguistic study to confirm. The founding of Al-Azhar Mosque in 970 AD was not merely the construction of a religious building, but the creation of a towering monument to the Arabic language, which produced brilliant scholars.

The Edict of Theodosius I

Al-Azhar Mosque, founded in 970 AD, was not merely a religious building, but a towering monument to the Arabic language, which produced brilliant scholars. But before the emergence of this edifice, have we considered the profound transformations that Egypt underwent, which changed its linguistic and cultural landscape? In the fourth century AD, with the conversion of Christianity to the official religion of the Roman Empire, the ancient Egyptian religion began to decline. The Edict of Theodosius I in 391 AD was a devastating blow, as it prohibited pagan practices and closed the temples, whose sacred language, its lifeblood, was hieroglyphics.

At this point, hieroglyphics began to lose their primary function as a religious language, and with it, their social importance diminished, like a sun setting below the horizon. This decline was not the result of a top-down decision or direct suppression, but rather the result of gradual shifts within Egyptian society. Coptic, Greek, and Arabic all played roles in this complex transformation, but they were merely tools in the hands of greater forces, namely the relentless forces of cultural, religious, and social change.

Conclusion

Ultimately, the decline of hieroglyphics does not represent failure or defeat, but rather transformation. It is a story that reflects Egypt’s resilience and ability to adapt to the changes of time. The Arab conquest was not the final blow, but the final scene in a long and complex drama. A drama whose protagonists are not