Pre-Columbian Muslim Presence in the Americas: Evidence from Historical Maps.

Pre-Columbian Muslims in America? Ancient Maps Speak

History books celebrate Columbus’s daring voyage and the discovery of the New World. However, this narrative may be incomplete. Could Islamic scholars, driven by the intellectual fervor of their Golden Age, have charted the western seas centuries before Columbus’s expedition? We investigate the subtle indications etched onto ancient maps, the cryptic symbols within medieval texts, and the tantalizing fragments of forgotten voyages. Are these mere coincidences, elaborate fabrications, or concrete evidence that the accepted historical account is inaccurate? The answer lies not in blind faith, but in the rigorous examination of historical cartography and the forgotten documents that hint at a past yet to be fully revealed. Join us as we navigate the challenging terrain of historical revisionism and prepare to question established truths.

As we unearth these forgotten voyages, what other established historical narratives might be challenged? Subscribe to our channel now and witness history revealed. Share your initial thoughts on this historical puzzle in the comments below.

The Golden Age of Islamic Seafaring

To fully appreciate the possibility of pre-Columbian contact, we must first understand the remarkable advancements in Islamic seafaring during its Golden Age. Ninth-century Baghdad, a center of intellectual pursuit, housed the House of Wisdom. Here, scholars meticulously translated Greek astronomical and geographical texts, including Ptolemy’s *Almagest* and *Geography*, establishing a foundation for a scientific revolution in cartography. Al-Biruni, an 11th-century polymath, calculated the Earth’s circumference with astonishing accuracy, demonstrating profound geodetic knowledge that remains impressive today.

Beyond theoretical knowledge, they mastered the seas. Consider Ahmad Ibn Majid, the 15th-century navigator whose *Book of Useful Information* – a comprehensive encyclopedia of Indian Ocean navigation – detailed monsoon winds, star positions, and intricate coastal routes. The development of the kamal, a simple yet effective instrument, allowed sailors to measure latitude with unprecedented accuracy, enabling them to traverse vast stretches of ocean. The astrolabe, a marvel of engineering, facilitated precise timekeeping and celestial navigation. Their ingenuity extended to shipbuilding. The dhow, with its distinctive lateen sail and robust construction, became the workhorse of the Indian Ocean, facilitating trade and exploration across continents – a testament to maritime prowess. Could these vessels, guided by this profound knowledge, have sailed west, beyond the known horizon, into the “sea of darkness,” as described in some Arabic texts, toward a land of gold and indigenous peoples? The question remains, echoing across the centuries.

The Enigmatic Piri Reis Map

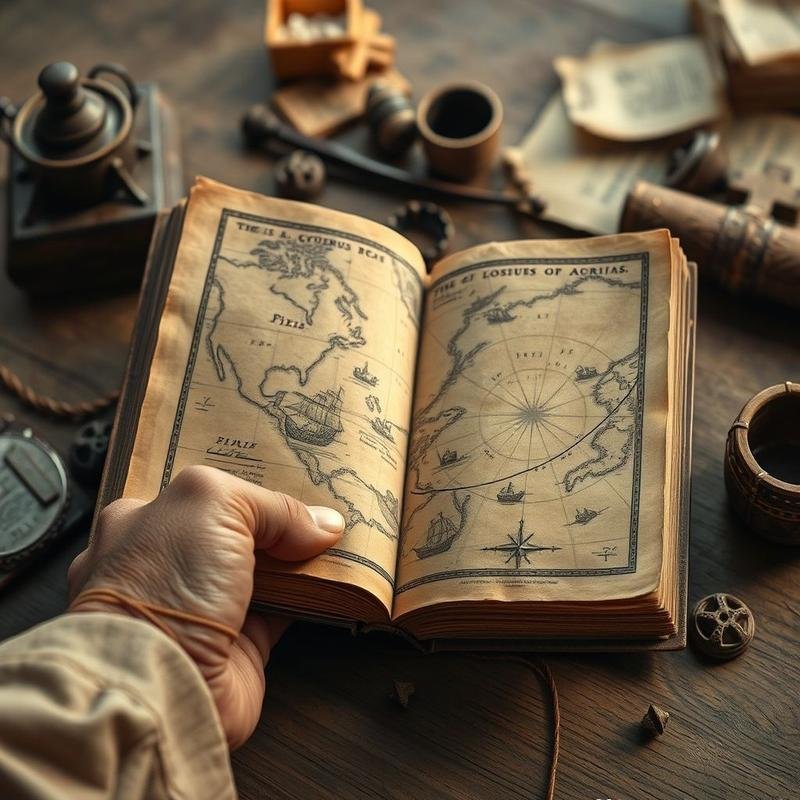

A subtle indication from the past takes form: the Piri Reis Map. Discovered in 1929 during the reorganization of Istanbul’s Topkapi Palace Library, this fragment of gazelle skin parchment, dated 1513, presents a cartographic enigma. Only the western third of the original survives, yet it holds secrets that continue to spark debate. What mysteries lie hidden within its faded lines?

Piri Reis, an Ottoman admiral and cartographer, explicitly states in the map’s detailed marginal notes, written in elegant Turkish script, that his creation is a compilation, drawing upon approximately twenty older maps, a mosaic of ancient knowledge. Eight of these were Ptolemaic, reflecting the classical Greek understanding of the world. Four were contemporary Portuguese charts, testaments to Europe’s burgeoning age of exploration. And one, crucially, was an Arabic map of India – a complex tapestry woven from diverse sources.

The depiction of South America ignites the most fervent speculation. The coastline is remarkably detailed, including the Andes Mountains, whose European discovery postdates the map by over a decade. How could Piri Reis possess such precise information? Did he have access to sources unknown to his contemporaries, lost to time? More controversially, some argue that the map accurately depicts the coastline of Antarctica, centuries before its supposed official discovery, and in an ice-free state, implying knowledge predating any known civilization – a theory dismissed by many mainstream cartographers. This tantalizing prospect hints at lost knowledge, advanced surveying techniques, and a world perhaps far more interconnected than previously imagined. Is it a genuine window into a forgotten past, a key unlocking ancient secrets, or a tantalizing illusion, a mirage built on misinterpretation and conjecture? The debate continues, fueled by each careful examination of this enigmatic artifact. Is it truth, or a carefully constructed fabrication? The fine lines of the map itself offer no easy answers, only deeper questions.

Subtle Indications and Unproven Encounters

Beyond the map’s familiar edges, subtle indications persist of unproven encounters. Columbus himself, ever the keen observer, noted gold ornaments among Native Americans, strikingly similar to those of Guinea – a tantalizing hint of a West African presence, perhaps linked to the sprawling Muslim empires of the age. Was this mere chance, a fleeting resemblance, or could it be a tangible echo of Abu Bakr II, the Malian Emperor who, in 1311, according to the Arab historian al-Umari, relinquished his throne to command a fleet across the vast Atlantic? No definitive archaeological evidence has surfaced to confirm this daring voyage, leaving it veiled in the alluring mists of legend. Yet the possibility remains, a siren song luring us further into the unknown.

Further south, in 1511, Peter Martyr d’Anghiera, chronicler of the Spanish court, meticulously documented the sophisticated canoes and intricate trading networks of indigenous peoples, a testament to a maritime prowess that some believe could have propelled transoceanic contact. However, does such skill, however impressive, inherently confirm a Muslim connection? The transition from capability to contact requires more substantial evidence.

Even more enigmatic is the Bat Creek Stone, unearthed in Tennessee in 1889. Its inscription, initially hailed as Paleo-Hebrew, ignited speculation of pre-Columbian Semitic visitors. Yet, mainstream archaeology casts a skeptical eye, leaning towards forgery or simple misinterpretation. A similar tale unfolds around Newport’s Moors Tower in Rhode Island, occasionally attributed to Muslim explorers, though the prevailing theory points to construction by Norse or later European settlers. The lack of definitive context plagues these isolated finds.

What of those Roman coins, purportedly discovered in the depths of Venezuela? Such finds, while undeniably tantalizing, suffer from a critical flaw: a lack of verifiable provenance, raising persistent doubts about their later introduction. Even genetic studies, pointing to the presence of certain haplogroups common in the Middle East within Native American populations, remain hotly debated, their conclusions weakened by small sample sizes and alternative, equally plausible explanations. Each piece – a fragment, a shadow – holds the potential for illumination, but ultimately demands rigorous, unwavering scrutiny before we can accept it as definitive proof. The danger lies in allowing tantalizing possibilities to overshadow rigorous methodology.

Columbus and Hidden Knowledge

Could Columbus himself have possessed knowledge obscured by time? His personal copy of Pierre d’Ailly’s *Imago Mundi*, heavily annotated, reveals a fascination with a smaller Earth, influenced by Arab astronomers like Al-Farghani. Columbus’s underestimation of the Earth’s circumference stemmed partly from his reliance on a flawed interpretation of Al-Farghani’s degree measurement. Intriguingly, a world map attributed to Columbus, dating back to 1491, depicts a landmass west of the Azores, fueling speculation about pre-existing awareness of the Americas. But where did this awareness originate? Further subtle indications emerge from Columbus’s own journal, where he recounts tales from Caribbean natives of traders arriving from the southeast in grand canoes, bearing white cotton – a tantalizing hint of contact with distant cultures, unknown cultures. Even the celebrated Piri Reis Map, compiled in 1513 using captured charts from Columbus’s voyages, displays a remarkably accurate South American coastline. Did Columbus stumble upon forgotten maps, perhaps charting courses charted long before? Or did he simply benefit from the accumulated, undocumented knowledge of mariners from distant shores, riding the winds and currents others had already dared to navigate? The question remains: what hidden currents propelled his journey, and whose maps guided his hand?

The Skeptic’s Perspective

However, the theory is not without its critics. Claims of Arabic inscriptions predating Columbus, for example, often spark alternative interpretations. What one observer perceives as elegant Arabic script, another discerns as stylized indigenous art, or even the random artistry of nature etched in rock. The eminent historian Bernard Lewis famously argued that evidence for pre-Columbian Muslim contact remains anecdotal, frustratingly lacking the serious documentary confirmation that would silence doubt. Consider Columbus’s own diary; it mentions a mosque on Cuba. Could this be a literal house of worship, or simply a metaphor, a European observer’s way of describing unfamiliar, striking architectural features? The ambiguity inherent in historical interpretation demands caution.

Even genetic studies hinting at possible connections offer only fleeting, inconclusive glimpses and demand rigorous validation. One study, exploring mitochondrial DNA variations, tentatively suggested a Middle Eastern link. Yet, the sample size was limited, a frustrating constraint, and alternative explanations – the simple reality of later genetic mixing – cannot be dismissed. Claims of Arabic linguistic influence on Native American languages remain hotly contested, debated, and far from settled. Perhaps most tellingly, the absence of widespread Islamic cultural markers – distinct religious practices, recognizable dietary habits, identifiable artistic styles – presents a formidable challenge. Where are the grand mosques, the intricately designed Islamic pottery, the undeniable Arabic loanwords demonstrably present before Columbus’s arrival? As it stands, the evidence, while intriguing, stops short of definitive proof, leaving the debate unresolved. Absence of evidence is not evidence of absence, but it is a significant hurdle to overcome.

Conclusion

While captivating, the question of pre-Columbian Muslim contact remains shrouded in ambiguity. The Piri Reis Map, with its startlingly accurate South American coastline, fuels speculation, yet its interpretation is fiercely contested. Arabic texts hinting at new lands predate 1492, but how geographically specific are they, really? Columbus himself alluded to prior knowledge, and Zheng He’s voyages undeniably demonstrated maritime capabilities, but definitive proof… it continues to elude us.